Massage and Shoulder Dysfunction

The following is an excerpt taken from the November 2016 Massage Therapy Journal written by Christian Bond.

Whether you pull a muscle, have an overuse injury or strain, or are dealing with any number of issues, one thing typically remains true: You never really understand how much you use your shoulder, hip or knee until you’re dealing with chronic pain or injury.

Shoulder injuries and strains are common for many people, and according to George Russell, a massage therapist and chiropractor in New York City, massage therapy can be ideal for helping those who suffer from shoulder dysfunction.

Anatomy and Structure

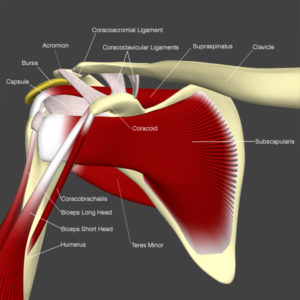

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles— supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis—whose fibers emerge directly from all over the shoulder blade and converge on the humeral head. These muscles are called a cuff because they attach like a cuff to the very outer top of the humerus. “Picture an epaulet on a military jacket,” Russell suggests. When contracted, these same muscles rotate the humerus, which is why the group of muscles is called the “rotator cuff.”

But that’s not all they do, and “rotator” may not even describe their primary function. “It’s true they move the humerus in various ways, especially rotation,” Russell says. “But kinesiology reveals the rotator cuff’s real function—to snug the humeral head into the middle of its shallow socket on the outside of the shoulder blade, no matter where the arm moves in space.”

Like a mortar and pestle, the shoulder joint (like any ball-and-socket joint) functions through roll and glide. When you lift your elbow over your head, the humeral head rolls up in the socket and would roll out and hit the acromion if there weren’t an equal and opposite glide down in the socket. The opposing glide is what keeps the joint from harm, and that glide is the job of the rotator cuff. “The rotator cuff muscles come off almost every surface of the scapula— front, back and top,” explains Russell. “That pattern of attachment suggests that the scapula is the stable end of the muscles and the ‘cuff’ all around the outer top of the humerus is what is moved—in whatever way glides the humeral head to the center of the glenoid fossa.” Think, for example, of a professional baseball player pitching a fastball: The rotator cuff is what keeps his arm from flying over home plate with the baseball. “When Masahiro Tanaka throws his fastball, the rotator cuff pulls the humeral head backward and toward his scapula, gliding the humeral head back into the center of the socket where it belongs,” Russell says.

Common Injuries

Instead of starting by releasing spasm and tightness in the rotator cuff, consider the shoulder joint itself as a whole. “In my opinion, all of the common injuries of the shoulder result from shoulder joint misalignment,” Russell says. “The rotator cuff becomes damaged when it tries its hardest—but fails—to glide the humeral head to the center of the socket.” Following are some of the most common shoulder injuries.

A SLAP tear (superior labral tear from anterior to posterior) is a tear of the superior labrum and, often, the long head of the biceps. The labrum is a ring of cartilage that deepens the socket for more controlled movement. In a SLAP tear, the bone rolls up to move the whole arm up in space, but for some reason, the rotator cuff fails to counter the force of that movement so there’s equal glide back into the socket. The labrum is the next line of defense, and it should act like a guardrail on a highway, bouncing the ball back into the socket. “But you can only drive so long against a guardrail before it gives,” Russell explains. Sooner or later, the humeral head will breach the labrum, and it almost always starts at the top and front of the joint, where the ligamentous and joint capsule protection is the least and where the human arm tends to go.

Acromial impingement, shoulder bursitis, and supraspinatus or other rotator cuff muscle tendonitis/tear. All of these injuries have to do with the failure of downward/backward glide, which is also a failure of all the rotator cuff muscles. “Powered by the deltoid, the humerus rolls up to bring the arm overhead,” Russell explains. “If the rotator cuff cannot or does not glide the ball down into the glenoid fossa, the bone eventually hits the acromion, which sits above the humeral head like a carport above a car.” Damage to any structure from the humeral

head to the acromion can result. Eventually, one can expect arthritis as well, since a poorly seated joint doesn’t allow the cartilage surfaces to stay against one another and to be nourished by the joint fluid.

Who Gets Rotator Cuff Injuries

As might be expected, Russell explains, anyone whose work requires that they have their hands above their heads for long periods of time are prone to rotator cuff injuries. “The rotator cuff is ‘white meat’ muscle. It has no myoglobin, so it can’t burn glucose for energy. It’s like it’s on battery power (glycogen),” he says. “When the battery runs out, the liver needs a half hour to recharge the battery, so if you’re going past that deadline again and again, you’ll get overuse syndromes and fascial adhesions.”

Athletes who throw, too, are more likely to have rotator cuff problems because the rotator cuff is the structure that decelerates the arm once you’ve let go of what you’re throwing. “To throw with any power, you usually rotate your body,” Russell adds. “This means that the rotator cuff often has to work around a corner or at some odd angle because the shoulder blade is very protracted and the ribcage is rotated as well.”

Russell also notes that swimmers are at risk for shoulder problems because of the big range of motion they take their arms through against the resistance of the water, while also rotating their neck and ribcage. “It’s a complex task,” Russell says, “and can lead to rotator cuff strain, especially in the subscapularis, which stabilizes while it also assists internal rotation of the arm as you push the water back with the arm.”