The following is an article written by Linda Fehrs, LMT in 2010 on the subject of CRPS or complex regional pain syndrome.

Chronic pain is a complaint massage therapists hear from many clients. The causes vary from pain as a result of injury or accident to post-surgery pain. There may be times that the actual cause is unknown or elusive. Learn more about complex regional pain syndrome, a chronic and often debilitating form of pain that may be helped by the use of massage therapy.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic and progressive collection of pain symptoms characterized by severe, burning pain, tissue damage, stiffness, changes in skin texture/color (thin, shiny, blotchy, blue, purple, or red), temperature and/or swelling and extreme sensitivity to touch (allodynia). Persons afflicted with this disorder say that sometimes the pain is so bad it is like being doused with gasoline and set on fire.

There are two similar forms of CRPS, CRPS-1 and CRPS-II both with the same symptoms and treatments. CRPS-1 (previously called reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome) is the term given for individuals without confirmed nerve injuries, while CRPS-II (previously called causalgia) is the term for those with confirmed nerve injuries.

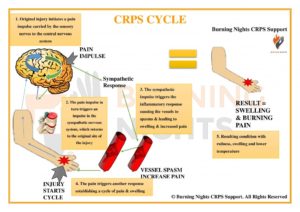

What Causes CRPS?

Unlike some chronic pain disorders, the pain of CRPS is triggered by a misfiring of nerves within the nervous system that, in turn, send constant pain signals to the brain. In more than 90% of cases, the initial trigger was a trauma or a minor injury, such as a sprain/strain, fracture, soft tissue injury (burn, cuts, bruises), fall or other physically traumatic event, including certain medical procedures.

Because chronic pain lasts for a long time, it can cause changes in the brain, which can consequently be responsible for changes in how the body functions. For example, a person with chronic pain might have trouble figuring out right and left side discrimination. Another change, called tactile discrimination, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to figure out what is touching the body in the area of the chronic pain. The brain cannot interpret whether something touching the body is soft or hard, pointy or dull. This might lead to an inability to be aware of an object causing even further injury to the body.

Because chronic pain lasts for a long time, it can cause changes in the brain, which can consequently be responsible for changes in how the body functions. For example, a person with chronic pain might have trouble figuring out right and left side discrimination. Another change, called tactile discrimination, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to figure out what is touching the body in the area of the chronic pain. The brain cannot interpret whether something touching the body is soft or hard, pointy or dull. This might lead to an inability to be aware of an object causing even further injury to the body.

How Can Massage Help?

Persons with CRPS tend to have more than just moderate aches and pains. It is less generalized than fibromyalgia. At times the pain is excruciating, mostly in the arms and/or legs. Even light touch, such as clothing touching the body, can be irritating.

So how can massage, which consists mainly of touch, be helpful? A person with CRPS may have periods of less intense pain. This would be the time to introduce therapeutic massage, perhaps beginning with less intrusive modalities such as cranial-sacral techniques or polarity massage. At the very least, these techniques help a person to relax and refocus away from the pain.

Massage therapists can also educate their clients on maintaining proper body alignment, which will help avoid postural guarding of the affected limb and promote a more balanced use of muscles. Instructing clients on the importance of exercise is also important in the fight against pain. Exercise, as well as massage therapy, can increase the body’s production of endorphins and serotonin, both of which contribute to not only elevating a person’s mood, but also act as natural pain killers helping to block pain signals to the brain. Exercise can also help to reeducate the body with regard to special awareness or proprioception. If a person cannot do strenuous exercise, suggest something like Tai Chi or Qigong, which can help to improve balance, flexibility and the flow of energy within the body.

In addition to exercise, receiving various forms of massage therapy can help with proprioception and the re-training of the mind-body connection. Techniques such as lymphatic drainage can reduce edema and thus reduce pain that might be triggered by the pressure of built up fluid in the extremities, while neuromuscular techniques can help inhibit the pain-spasm-pain cycle.

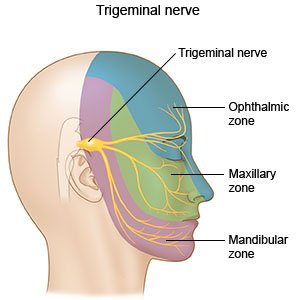

forehead, temple region, and jaw. She told me she had been diagnosed with Trigeminal Neuralgia and was seeking help from therapeutic massage. Since this was something I had not dealt with in the past we attempted a very short therapeutic treatment for her first session. But I immediately did some research and learned a good deal about this terrible condition and wanted to post something for those of you who may be suffering and looking for an alternative means of relief.

forehead, temple region, and jaw. She told me she had been diagnosed with Trigeminal Neuralgia and was seeking help from therapeutic massage. Since this was something I had not dealt with in the past we attempted a very short therapeutic treatment for her first session. But I immediately did some research and learned a good deal about this terrible condition and wanted to post something for those of you who may be suffering and looking for an alternative means of relief. experience treating patients with TN. A few simple treatment procedures will be discussed, and I believe they are worth a try for therapists to see if they also have positive effects in treating this nerve pain.

experience treating patients with TN. A few simple treatment procedures will be discussed, and I believe they are worth a try for therapists to see if they also have positive effects in treating this nerve pain. Even more significant, the

Even more significant, the  While seated or standing, raise your arm to 90 degrees with your elbow also bent to 90 degrees (as shown). Fold your fingers down so that the pads of your fingers touch your hand. Make sure the wrist and fingers are straight. A Passing result is if all the fingers touch the hand.

While seated or standing, raise your arm to 90 degrees with your elbow also bent to 90 degrees (as shown). Fold your fingers down so that the pads of your fingers touch your hand. Make sure the wrist and fingers are straight. A Passing result is if all the fingers touch the hand. A Not Passing result is if one or more fingers cannot reach the hand (keeping wrist and fingers straight), indicating trigger points in the Scalenes.

A Not Passing result is if one or more fingers cannot reach the hand (keeping wrist and fingers straight), indicating trigger points in the Scalenes.

The Scalenes can be palpated on the sides of the neck, in the space just in front of the bony vertebra and just behind the thick

The Scalenes can be palpated on the sides of the neck, in the space just in front of the bony vertebra and just behind the thick  Positioning your chosen self-care tool as shown, cover the entire length of the Scalenes, looking for taut bands and tender spots. When you find a tender spot, press into the muscle to pain tolerance (“good pain” – not pain that is sharp or makes you want to withdraw). Hold for 10 seconds while completing at least two full breaths in and out. Then continue searching for more tender spots until the entire Scalenes muscle group is covered.

Positioning your chosen self-care tool as shown, cover the entire length of the Scalenes, looking for taut bands and tender spots. When you find a tender spot, press into the muscle to pain tolerance (“good pain” – not pain that is sharp or makes you want to withdraw). Hold for 10 seconds while completing at least two full breaths in and out. Then continue searching for more tender spots until the entire Scalenes muscle group is covered. Using a stretching strap or jump rope, step on one section of the rope and hold the other end with your hand so that the rope is taut (as Shown). You should feel a gentle pull on your shoulder down toward the floor.

Using a stretching strap or jump rope, step on one section of the rope and hold the other end with your hand so that the rope is taut (as Shown). You should feel a gentle pull on your shoulder down toward the floor.

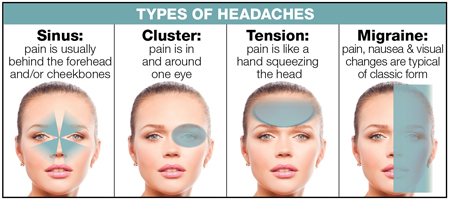

resources that indicate that massage therapy is very helpful in alleviating and even, possibly, preventing headaches.

resources that indicate that massage therapy is very helpful in alleviating and even, possibly, preventing headaches.